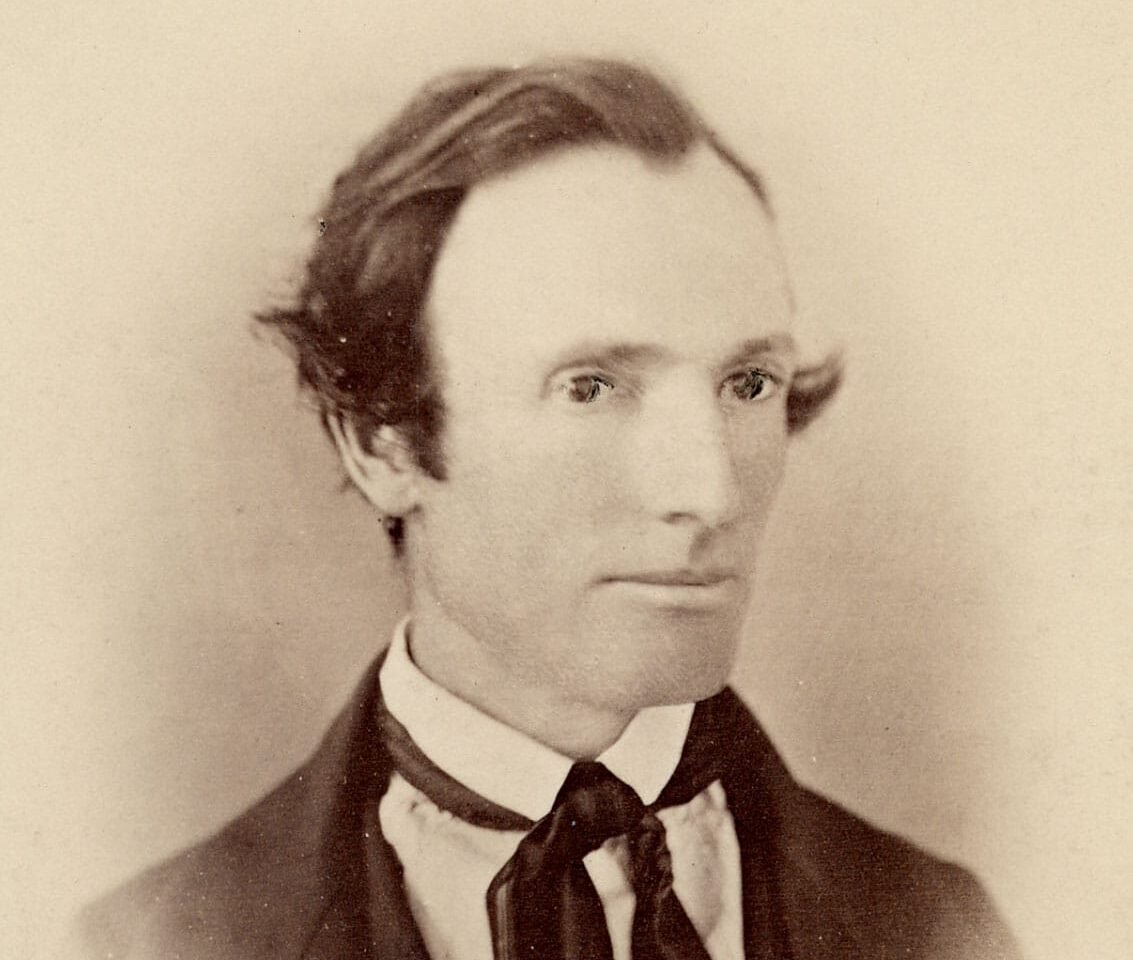

Oliver Cowdery is one of the most prominent figures in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was present for the translation of the Book of Mormon, the restoration of the Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthoods, and the visitation of Jesus Christ in the Kirtland Temple.

Most members know that Oliver left the church, but why did he leave? If he was present for all these significant events, what would motivate him to give it up? Although that topic would be better served by a professional historian, in this brief post I attempt to give some insight into his departure.

I believe Oliver’s example is a powerful witness of the truthfulness of the claims of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His story is an example of our frailties as humans, our imperfections even in the governance of the church, and of the Savior’s infinite patience and willingness to forgive. In Oliver’s life, I see examples of faith, hope, and humility.

Oliver’s early life

Oliver Cowdery was born on October 3, 1805, in Wells, Vermont, to his parents William Cowdery and Rebecca Fuller.1 Rebecca died on September 3, 1809, when Oliver was not yet 4 years old. Less than a year later, on March 18, 1810, William married Keziah Pearce Austin.2

After his mother’s death, it appears that Oliver lived with his mother’s older sister and her husband, Hulda and Rufus Glass. The Glass and Cowdery families were neighbors, and it may be that Oliver lived with them from 1809 to 1813, then again from 1820 to 1822.3 Hulda died on March 21, 1813, and Rufus died just two weeks later. That could be when Oliver returned to live with his father. Oliver’s cousin, Arunah Glass, was 17 years old at the time, and became the primary caretaker for his younger siblings. The belief that Oliver lived with them in 1820 is based on school records, indicating that Oliver’s father sent him to live with his cousins to attend school.4

There are not many details about his early life, other than the tragedies in the deaths of his mother, aunt and uncle. But his father, William, came from a religious and educated family. William Sr., Oliver’s grandfather, was a deacon in the Reading, Vermont, Congregational Church.5 It seems that Oliver’s family valued education, as at least four of William Jr.’s six sons (including Oliver) became either doctors or lawyers.6

Meeting the Smiths

Oliver arrived at the Smith home in Palmyra, New York, in 1829. Lucy Young, (Oliver’s half-sister who married Phineas Young, the brother of Brigham Young), said that Oliver left Vermont and moved to upstate New York when he was twenty, making the move in 1826 or 1827.7 Oliver’s brother Lyman applied to teach school in the Manchester district, where Joseph Smith’s brother Hyrum was a trustee of the school.8 But after the school district agreed to employ Lyman, he asked that they accept Oliver as the teacher in his place.9 After interviewing Oliver, they discovered that he “had acquired a good common school education,” and “all parties were satisfied” that Oliver could handle himself well as a teacher.10

Oliver taught in a small schoolhouse about a mile south of the Smith home. He taught for about five months, beginning in late October 1828.11 His students included Joseph Smith’s siblings Katharine, Don Carlos, and Lucy, who were all younger than sixteen.12 He frequently asked his students to read from the New Testament, and he had a good reputation (one student remembered him as a “peacable fellow.”)13 Of course, in that proximity to the Smith family, and having several of the Smith children as his students, Oliver would have heard the rumors of Joseph Smith and the “gold Bible.”

The details and dates aren’t known, but at some point Oliver asked Joseph Smith Sr. if he could stay at the Smith home as a boarder.14 Oliver asked the Smiths questions about Joseph’s experiences, but they were reluctant to share any information. Lucy (Joseph’s Mother) simply states, “[Oliver] had been in the school but a short time, when he began to hear from all quarters concerning the plates, and as soon began to importune Mr. Smith upon the subject, but for a considerable length of time did not succeed in eliciting any information. At last, however, he gained my husband’s confidence, so far as to obtain a sketch of the facts relative to the plates.”15

After hearing about Joseph’s experiences, Oliver sought to know of their truthfulness. After Oliver met Joseph in April 1829, Joseph received a revelation now known as Doctrine and Covenants 6, in which the Lord said to Oliver, “[C]ast your mind upon the night that you cried unto me in your heart, that you might know concerning the truth of these things.”16 Later, Joseph Smith wrote about that revelation and the experience Oliver had in praying to know the truth: “[A]fter Oliver had gone to my father’s to board, and after the family communicated to him concerning my having got the plates, that one night after he had retired to bed, he called upon the Lord to know if these things were so, and that the Lord had manifested to him that they were true, but that he had kept the circumstance entirely secret, and had mentioned it to no being, so that after this revelation having been given, he knew that the work was true, because that no mortal being living knew of the thing alluded to in the revelation but God and himself.”17

In an earlier writing, Joseph was more explicit about the revelation that Oliver had received: “[The] Lord appeared unto a young man by the name of Oliver Cowd[e]ry and shewed unto him the plates in a vision and also the truth of the work and what the Lord was about to do through me his unworthy Servant therefore he was desiorous to come and write for me and to translate.”18

Lucy (Joseph’s mother) wrote that after hearing about Joseph, “Oliver was so entirely absorbed in the subject of the record that it seemed impossible for him to think or converse about anything else.”19

Oliver meets Joseph

After hearing from the Smiths about Joseph’s experiences, and after receiving a testimony of Joseph’s calling, Oliver traveled from Palmyra to Harmony, Pennsylvania, and almost immediately started acting as scribe for Joseph Smith in the Book of Mormon translation. It is well-documented that his work as scribe began on April 7, 1829.20 He was with Joseph when John the Baptist appeared to them to confer upon them the Aaronic Priesthood, and he was with Joseph when Peter, James, and John appeared to them to confer upon them the Melchizedek Priesthood. He was also one of the three witnesses of the Book of Mormon.21

Oliver was heavily involved in the printing of the Book of Mormon. Likely because of the loss of the 116 pages, rather than give the printer the original manuscript, Oliver prepared a “printer’s manuscript” of the Book of Mormon.22 Based on the handwriting, it is apparent that Oliver wrote 84 percent of the printer’s manuscript.23 John Gilbert primarily set the type for the printing, but Oliver Cowdery set the type for a few pages.24 Oliver acted as a printer for many subsequent church publications, and it seems he learned that skill while observing and helping with the printing of the Book of Mormon.

The Church was organized on April 6, 1830. In a revelation given in advance of that event, Oliver was identified as an “apostle of Jesus Christ,” and the “second elder” of the Church.25

Oliver’s mission to Ohio

In September 1830, Joseph received a revelation that instructed Oliver to “go unto the Lamanites and preach my gospel unto them.”26 Interestingly, this is the same revelation that lets us know that Hiram Page, one of the eight witnesses of the Book of Mormon, had claimed to receive revelations, and he was so convincing that Oliver believed him.27 It is worth noting that Hiram Page married Catherine Whitmer, the sister to David Whitmer, and Oliver’s eventual wife Elizabeth Whitmer.28 Oliver’s close relationship with the Whitmer family could be the eventual cause of his departure from the Church, and it could explain his support of Hiram. However, the revelation instructing Oliver to preach the gospel to the Lamanites told him, “no one shall be appointed to receive commandments and revelations in this church excepting my servant Joseph Smith, Jun.”29

What might Oliver have thought about that? Oliver had been with Joseph during all major events of the restoration. Now, in the same revelation, he was told that Joseph was the only one to receive revelations and commandments, and he was sending Oliver away. Whatever Oliver thought about it, he went.

In another revelation in October 1830, Parley P. Pratt and Ziba Peterson were told to go with Oliver and Peter Whitmer “into the wilderness among the Lamanites.”30 At that time, territory in Kansas and Ohio had been set aside for the American Indians.31 So as the four missionaries traveled toward those territories, they passed through Ohio, where they visited Sidney Rigdon, who was a friend of Parley P. Pratt.32 In his autobiography, Pratt recounts that “the news of the discovery of the Book of Mormon and the marvellous events connected with it” created a general “interest and excitement … in Kirtland, and in all the region round about. The people thronged us night and day, insomuch that we had no time for rest and retirement.”33 This tremendous success resulted in Sidney Rigdon and Frederick G Williams joining the church.

I wonder if Oliver saw Sidney Rigdon as a rival. After Sidney’s baptism, Sidney traveled to New York to meet Joseph, and he began working with Joseph on the translation of the Bible. Had Oliver, who had been so close to Joseph prior to his mission, been replaced? Despite Oliver’s tremendous success as a missionary, did he feel like he had been cast aside?

After leaving Ohio, Oliver and his companions were accompanied by Frederick G. Williams.34 They preached to several congregations in Indian Territory, including the Shawnees and the Delawares.35 There was some interest, but by order of a federal agent, the missionaries were expelled from Indian Territory.36

Oliver’s life in Missouri

After the successful mission in Ohio, Oliver performed many responsibilities in the fledgling church, but it seems that one of his most prominent was as a printer. In November 1831, Joseph Smith and other leaders of the Church determined to print the revelations that had been received.37 William W. Phelps had established a printing press in Missouri, and Oliver was appointed to take the revelations to Missouri for printing.38

While in Missouri, Oliver helped William W. Phelps with the Church’s printing operations, including editing the newspaper The Evening and the Morning Star.39 It was in Missouri that Oliver married Elizabeth Ann Whitmer, the sister of David Whitmer.40

Although there is no historical record to confirm this, I can’t help but wonder if this time separated from Joseph created feelings of frustration for Oliver, and whether he looked at Sidney Rigdon as a rival, or even a usurper. It is fascinating to me that Oliver was ordained a high priest by Sidney in August 1831.41 Would that have seemed wrong to Oliver? Oliver had been called the “second elder” of the Church, and was with Joseph during the major events of the restoration. And yet, Joseph had sent Oliver away, and he continued receiving revelations in Oliver’s absence, including revelations regarding the continued development of the high priesthood. Would it have been difficult for Oliver, who had received the Melchizedek Priesthood under the hands of Peter, James, and John, to be ordained a high priest by Sidney Rigdon?

Tensions in Missouri were increasing, and in July 1833, a mob destroyed the printing press in Independence.42 Shortly after that, Oliver moved back to Kirtland, and he continued the printing efforts in Kirtland.43

Oliver’s return to Kirtland

It seems that once he was back in Kirtland, Oliver resumed his place as second only to Joseph in the Church. He became a member of the United Firm, the Literary Firm, and the Kirtland high council.44 When Joseph Smith organized a group to try and reclaim Zion (known as “Zion’s Camp,”) Oliver and Sidney stayed behind in Kirtland to supervise the construction of the temple and direct the other affairs of the Church.45

On December 5, 1834, Oliver was appointed as an assistant president of the Church.46 Oliver continued as the primary historian, and his entry in the history for that day provides some insight into how he might have felt about his time in Missouri (spelling and grammar are corrected for ease of reading):

“Friday Evening, December 5, 1834. According to the direction of the Holy Spirit, President Smith, assistant Presidents, Sidney Rigdon and Frederick G. Williams, assembled for the purpose of ordaining first High Counsellor Oliver Cowdery to the office of assistant President of the High and Holy Priesthood in the Church of the Latter-Day Saints. . . . The office of Assistant President is to assist in presiding over the whole church, and to officiate in the absence of the President, according to his rank and appointment, viz: President Cowdery, first; President Rigdon Second, and President Williams Third, as they were severally called. . . .

“The reader may further understand, that the reason why High Counsellor Cowdery was not previously ordained to the Presidency, was, in consequence of his necessary attendance in Zion, to assist Wm W. Phelps in conducting the printing business; but that this promise was made by the angel while in company with President Smith, at the time they recievd the office of the lesser priesthood. And further: The circumstances and situation of the Church requiring, Presidents Rigdon and Williams were previously ordained, to assist President Smith.”47

At least one author has seen in this entry that Oliver might have had some hard feelings about his separation from Joseph: “In the December 5, 1834, entry in the history, where Oliver was finally ordained an assistant president, he took pains to explain that he was deposed from this role only temporarily because of his absence in Missouri and that his rightful place was at Joseph’s side.”48

In a revelation given in June 1829, the Lord had instructed Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer (and later Martin Harris was also included in this instruction) to “search out the Twelve.”49 This charge was fulfilled on February 14, 1835, in a meeting called the “Meeting to choose the ‘Twelve.'”50 Joseph Smith asked all those brethren who “went to Zion” (or who were a part of Zion’s Camp) to “take their seats together.”51 The names of all those who went to Zion were taken (there were 56 present at the meeting), and Joseph then invited the “three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon to pray, each one, and then proceed to choose twelve men from the church as Apostles.”52 Each of the three witnesses prayed, then they were “blessed by the laying on of the hands of the Presidency.”53 The three witnesses then selected the twelve, who were: “1. Lyman E. Johnson; 2. Brigham Young; 3. Heber C. Kimball; 4. Orson Hyde; 5. David W. Patten; 6. Luke Johnson; 7. William E. McLellin; 8. John F. Boynton; 9. Orson Pratt; 10. William Smith; 11. Thomas B. Marsh; 12. Parley P. Pratt.”54

It was in this position as assistant president of the Church that Oliver experienced the glorious manifestation of the Savior in the Kirtland Temple on April 3, 1836, when he and Joseph also received priesthood keys from Moses, Elias, and Elijah.55 For a time, Oliver was where he felt he belonged in his position in the Church.

Trouble in Kirtland

It seems that Oliver’s troubles began while still in Kirtland, and they centered around the Kirtland Safety Society.

The fledgling Church was always in need of funds, but that need became acute in the mid-1830s. After the Saints were forced to leave Jackson County, they needed funds to acquire new land. People joining the Church were flocking to Kirtland, but it was primarily the poor who came, and the Church members didn’t have funds to help them.

Church leaders began buying land and goods on credit, and Oliver himself became deeply in debt as a result of these purchases.56 It is not known exactly when they came up with the idea, but Church leaders believed that founding their own bank would help resolve their financial crisis. Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery, Frederick G. Williams, Reynolds Cahoon, and David Whitmer were the original “committee of the directors” for the new bank.57

This topic is complicated, and to fully understand it requires knowledge of banking law and procedure (which I do not have). It became apparent that the Kirtland Safety Society would not be able to get a state banking charter, or at the very least, they would not get it quickly, so rather than become a bank, they changed their articles of agreement to simply be a financial institution. Under Ohio law, this required the officials (including Oliver) to be held personally liable for the redemption of all notes.58 However, without a charter, they became ineligible to receive federal monies being distributed to banks across the country at that time.59

Not long after the Safety Society opened, opponents of the Church moved to stop the Safety Society.60 For example, a man named Grandison Newell began as soon as the Safety Society opened to “drive about the country and buy up all the Mormon money possible, and the next morning go to the bank and obtain the specie.”61 Businesses began refusing to accept Kirtland’s banknotes. Meanwhile, Oliver had moved to Monroe, Michigan, and taken a position with the Bank of Monroe in an attempt to join efforts with the Kirtland Safety Society and strengthen both institutions. However, Oliver returned to Kirtland sometime during the spring of 1837, and he “found the city in turmoil.”62

A general economic collapse in the United States certainly did not help matters, and the founders of the Safety Society found themselves at odds. In a meeting held on Sunday, September 3, 1837, Oliver was sustained as an “assistant counselor” and one of the “heads of the Church,”63 but Joseph Smith apparently took issue with something Oliver had done, as he said, “Oliver Cowdery has been in transgression, but as he is now chosen as one of the presidents or counselors, I trust that he will yet humble himself and magnify his calling.”64

What transgression did Joseph imply? A historian wrote, “Oliver Cowdery’s feelings and behavior during this period remain obscure. A few weeks after he was sustained in his priesthood office, he was implicated in an alleged counterfeiting scheme led by Warren Parrish. Those leveling accusations acknowledged that the evidence was only circumstantial and hinged on the testimony of someone who was also involved in the plot. The unfounded accusations still helped blacken Oliver’s reputation.”65 His implication in counterfeiting, even though unfounded, haunted him and proved to be one of the grounds for his excommunication.

In the face of these difficulties, Oliver moved to Far West, Missouri, in August 1837.66

Oliver’s excommunication

It is significant to note that Oliver and David Whitmer were not just good friends, but brothers-in-law. Oliver knew David before he met Joseph Smith, and his wife was David’s sister. David became disaffected with Joseph Smith and the Church, and unlike Oliver, David wrote quite a bit about his reasoning. So it seems when the time came to choose sides, Oliver chose to align himself with David (just as he had previously given his support to Hiram Page). When Oliver moved back to Missouri in 1837, Joseph remained in Kirtland. I wonder what would have happened if Oliver had remained with Joseph, or if Joseph had been in Missouri.

The reasoning behind Oliver’s excommunication is largely one-sided. The Missouri high council created a record of why he was excommunicated, and Oliver wrote a response, but he didn’t appear at the meeting when he was excommunicated.

Perhaps because of the severe financial difficulties, once Oliver moved to Missouri, he began looking into practicing law. His interest in the law seemed to begin in Kirtland, when he was elected as a justice of the peace, and he served in that position from May 1837 until he left Kirtland and moved to Far West in August 1837.67 During just those three months, he heard 240 cases.68 In January 1838, Oliver wrote to his brother Warren that he had obtained some law books to study, and he seemed intent on practicing law.69 Also, again likely because of his financial difficulties, which occurred because of his service in the Church, Oliver tried to sell some land in Jackson County that was still held in his name.70 These two activities, his practice of law, and his efforts to sell land, largely constituted the charges against him that resulted in his excommunication.

On April 12, 1838, Oliver was tried before the high council in Far West. The minutes for the meeting state that Edward Partridge presided, and they brought the following charges (the spelling is verbatim from the minutes):

- 1st, For stiring up the enemy to persecute the brethren by urging on vexatious Lawsuits and thus distressing the inocent.

- 2nd, For seeking to destroying the character of President Joseph Smith jr, by falsly insinuating that he was guilty of adultry.

- 3rd For treating the Church with contempt by not attending meetings.

- 4th. For virtually denying the faith by declaring that he would not be governed by any ecclesiastical authority nor Revelation whatever in his temporal affairs.

- 5th For selling his lands in Jackson County contrary to the Revelations.

- 6th For writing and sending an insulting letter to President T[homas] B. Marsh while on the High Council, attending to the duties of his office, as President of the Council and by insulting the whole Council with the contents of said letter.

- 7th., For leaving the calling, in which God had appointed him, by Revelation, for the sake of filthy lucre, and turning to the practice of the Law.

- 8th, For disgracing the Church by lieing being connected in the ‘Bogus’ buisness as common report says.

- 9th. For dishonestly Retaining notes after they had been paid and finally for leaving or forsaking the cause of God, and betaking himself to the beggerly elements of the world and neglecting his high and Holy Calling contrary to his profession.71

Oliver did not appear at the hearing, but he sent a letter, which was read by Bishop Partridge, so it is included in the minutes of the hearing:

Far. West Mo April 12th 1838

Dear Sir.

I received your note of the 9th inst on the day of its date, containing a copy of nine charges prefered before yourself and Council, against me, by Elder Seymour Brunson.

I could have wished, that those charges might have been defered untill after my interview with President Smith; but as they are not, I must waive the anticipated pleasure with which I had flattered myself of an understanding on those points which are grounds of different opinions on some Church regulations, and others which personally interest myself.

The fifth charge reads as follows: “For selling his lands in Jackson County contrary to the revelations” so much of this charge, “For selling his lands in Jackson County” I acknowledge to be true, and believe a that a large majority of this Church have already spent their Judgements on that act, and pronounced it sufficient to warrant a disfellowship; and also that you have concured in its correctness-consequently, have no good reason for supposing you would give any decision contrary

Now sir the lands in our Country are allodial in the strictest construction of that term, and have not the least shadow of feudal tenours attached to them, consequently, they may be disposed of by deeds of conveyance without the consent or even approbation of a superior.

The fourth charge is in the following words, “For virtually denying the faith by declaring that he would not be governed by any ecclesiastical authority nor revelation whatever in his temporal affairs.” With regard to this, I, think, I am warranted in saying, the Judgement is also passed as on the matter of the fifth charge, consequently, I have no disposition to contend with the Council: this charge covers simply the doctrine of the fifth, and if I were to be controlled by other than my own judgement, in a compulsory manner, in my temporal interests. of course, could not buy or sell without the consent of some real or supposed authority. Whither that clause contains the precise words, I am not certain— I think howevere they were these “I will not be influenced, governed, or controlled, in my temporal interests by any ecclesiastical authority or pretended revelation what ever, contray to my own judgement” such being still my opinion shall only remark that the three great principles of English liberty, as laid down in the books, are “the right of personal security; the right of personal liberty, and the right of private property” My venerable ancestor was among that little band, who landed on the rocks of Plymouth in 1620— with him he brought those maxims, and a body of those laws which were the result and experience of many centuries, on the basis of which now stands our great and happy Goverment: and they are so interwoven in my nature, have so long been inculcated into my mind by a liberal and intelligent ancestry, that I am wholly unwilling to exchange them for any thing less liberal, less benevolent, or less free.

The very principle of which I conceive to be couched in an attempt to set up a kind of petty government, controlled and dictated by ecclesiastical influence, in the midst of this National and State Goverment. You will, no doubt say this is not correct; but the bare notice of those charges, over which you assume a right to decide, is, in my opinion, a direct attempt to make the secular power subservient to Church dictation— to the correctness of which I cannot in conscience subscribe— I believe that principle never did fail to produce Anarchy & confusion.

This attempt to controll me in my temporal interests, I conceive to be a disposition to take from me a portion of my Constitutional privileges and inherent rights— I only, respectfully, ask leave, therefore, to withdraw from a society assuming they <have> such right.

So far as relates to the other seven charges, I shall lay them carefully away, and take such a course with regard to them, as I may feel bound by my honor, to answer to my rising posterity.

I beg you, sir, to take no view of the foregoing remarks, other than my belief on the outward government of this Church. I do not charge you, or any other person who differs with me on those points, of not being sincere; but such difference does exist, which I sincerely regret.

With considerations of the hi[gh]est respect, I am, Your obedient servent. O Cowdery.72

After reading the letter, the high council presented testimony, which primarily asserted that Oliver “had been influential in causing lawsuits,” that he even issued “a writ on the Sabbath day,” that he “intended to form a partnership with Alexander Donophon,” that he wanted to “become a secret partner in the store as he would be able to collect the debts and act as an attorney and thereby be able to get his fees or living.”73 Several members of the Twelve testified that they had discussions with Oliver in which Oliver had accused Joseph of adultery.74

After additional testimony, the high council rejected the fourth and fifth charges, and the sixth charge was withdrawn, but the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 8th, and 9th charges were sustained, and Oliver was, therefore, “considered no longer a member of the Church.”75

Oliver leaves Missouri

Following his excommunication, Oliver remained in Missouri for a time, until tensions between members of the Church and Missouri residents turned violent. Two speeches by Sidney Rigdon seemed to push the conflict to a head.

In June 1838, Sidney gave a speech known as the “Salt Sermon.”76 He used Matthew 5:13 “ye are the salt of the earth,” and fairly inflammatory language, to argue that dissenters should be cast out from among the Saints.77 Shortly after this sermon, a letter dated June 17, 1838, was addressed to Oliver Cowdery, David and John Whitmer, W.W. Phelps, and Lyman E. Johnson.78

The letter threatened these individuals and demanded that they leave Missouri: “out of the County you shall go and no power shall save you, and you shall have three days after you receive this our communication to you including twenty-four hours in each day for you to depart with your families peaceably which you may do undisturbed by any person But in that time if you do not depart we will use the means in our power to cause you to depart for go you shall.”79 The letter was signed by 84 church members, including Sampson Avard, Philo Dibble, Amasa Lyman, Porter Rockwell, Levi Hancock, Newel Knight, Charles C. Rich, and Hyrum Smith.80

On July 4, 1838, Sidney Rigdon gave a fiery Fourth of July speech, captioned, “Better far sleep with the dead, than be oppressed among the living.”81 In this speech, Sidney said, “We have until this time, endured this great fight of affliction . . . . One cause of our heavy persecutions, is the influence which those have in the world, whom we have separated from the fellowship of the church for their wickedness; . . . We take God and all the holy angels to witness this day, that we warn all men in the name of Jesus Christ, to come on us no more forever, for from this hour, we will bear it no more, our rights shall no more be trampled on with impunity. The man or the set of men, who attempts it, does it at the expense of their lives. And that mob that comes on us to disturb us; it shall be between us and them a war of extermination, for we will follow them, till the last drop of their blood is spilled, or else they will have to exterminate us: for we will carry the seat of war to their own houses, and their own families, and one party or the other shall be utterly destroyed.”82

The letter had one intended effect. Oliver and the other “dissenters” left Far West.83 However, in another sense, the speech largely backfired. It prompted what came to be known as the “Mormon War,” the imprisonment of Sidney, Joseph, and others in Liberty Jail, the Extermination Order signed by Governor Boggs, and the expulsion of the Saints from Missouri.

Oliver’s practice of law

After leaving Far West, Oliver spent his remaining years practicing law, and being involved in politics. Oliver’s biography on the Joseph Smith Papers website has the following brief summary: “Driven from Far West, late June 1838. Moved to Richmond, Ray Co., Missouri, summer 1838. Returned to Kirtland, 1838, and briefly practiced law. Moved to Tiffin, Seneca Co., Ohio, where he continued law practice and held political offices, 1840–1847. Attended Methodist Protestant Church at Tiffin. Moved to Elkhorn, Walworth Co., Wisconsin Territory, 1847. Ran unsuccessfully for Wisconsin State Assembly, 1848. Coeditor of Walworth County Democrat, 1848.”84

William Lang, an attorney in Tiffin, Ohio, who studied law under Oliver’s supervision, wrote the following about Oliver’s time outside of the Church: “Mr. Cowdery was an able lawyer and a great advocate. His manners were easy and gentlemanly; he was polite, dignified, yet courteous. He had an open countenance, high forehead, dark brown eyes, Roman nose, clenched lips and prominent lower jaw. He shaved smooth and was neat and cleanly in his person. He was of light stature, about five feet, five inches high, and had a loose, easy walk. With all his kind and friendly disposition, there was a certain degree of sadness that seemed to pervade his whole being. His association with others was marked by the great amount of information his conversation conveyed and the beauty of his musical voice. His addresses to the court and jury were characterized by a high order of oratory, with brilliant and forensic force. He was modest and reserved, never spoke ill of any one, never complained.”85

Oliver’s return to the Church

Oliver’s return was largely facilitated by Phineas Young (Brigham’s brother, and the husband of Lucy Cowdery, Oliver’s half-sister).86 Phineas’ first visit to Oliver was in December 1842, and he then began writing the Twelve to report on his visits.87 This started a correspondence between Oliver, Phineas, and the Twelve, over the next several years. In one letter, Oliver wrote, “I believed at the time, and still believe, that ambitious and wicked men, envying the harmony existing between myself and the first elders of the church, and hoping to get into some other men’s birthright, by falsehoods the most foul and wicked, caused all this difficulty from beginning to end. They succeeded in getting myself out of the church; but since they themselves have gone to perdition, ought not old friends—long tried in the furnace of affliction, to be friends still.”88

Another statement by William Lang captured Oliver’s feelings upon hearing of Joseph’s death: “[Joseph] Smith was killed while [Oliver] C[owdery] lived here. I well remember the effect upon his countenance when he read the news in my presence. He immediately took the paper over to his house to read to his wife. On his return to the office we had a long conversation on the subject, and I was surprised to hear him speak with so much kindness of a man that had so wronged him as Smith had. It elevated him greatly in my already high esteem, and proved to me more than ever the nobility of his nature.”89

During their visits, it appears that Oliver persuaded Phineas of his innocence in many of the charges brought against him. In letters to the Twelve, Phineas blamed Thomas B. Marsh and others in conspiring to drive Oliver Cowdery out of the Church, and he believed that if the charges “were placed upon the heads of those apostates,” then Oliver would admit his shortcomings, make amends, and rejoin the Saints.90

However, it seems that the Twelve wanted Oliver to humbly return, regardless of how the Twelve might handle other dissenters. In a letter written in November 1847, Brigham Young said to Oliver, “[We] say to you in the Spirit of Jesus, . . . come for all things are now ready and the Spirit and the Bride say come, and return to our Father’s house, from whence thou hast wandered, and partake of the fatted calf and sup and be filled, and again be adorned with the Jewels of Salvation, and be shod with the preparation of the Gospel of Peace, by putting your hand in Elder [Phineas] Young’s and walking straightway into the Waters of Baptism, and receiving the laying on of his hands and the office of an Elder, and go forth with him and proclaim repentance unto this generation and renew thy testimony to the Truth of the Book of Mormon with a loud voice and faithful heart.”91

Oliver appears to have decided to rejoin the Saints in early 1848. He received help from a neighbor to outfit a team to move west with the Saints, and in October he sold some land to obtain additional funds for the move.92 Phineas and the Cowderys left the Cowderys’ home in Wisconsin, and arrived in Council Bluffs, Iowa, on October 21, 1848.93 The Saints were gathered in an “open-air” meeting, presided by Elder Orson Hyde. Recognizing Oliver, Elder Hyde stopped speaking, came off the stand, and embraced Cowdery.94 He led Oliver to the stand and after a brief introduction, invited Oliver to speak. A description of this moment was eloquently described by historian Scott Faulring:

“With overwhelming emotion swelling in his heart, yet in a clear and striking voice, Oliver Cowdery addressed this gathering of nearly two thousand people—the largest Mormon audience he ever spoke to. He bore a spontaneous yet lucid testimony of his personal involvement in the early years of the Mormon Church. Cowdery detailed the coming forth of the Book of Mormon and the restoration of the Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthoods. He reaffirmed his staunch belief in the Prophet Joseph Smith’s divine appointment and mission. Oliver recalled that years earlier he had laid hands on Elder Hyde’s head and ordained him to the priesthood and extended to him his call as an apostle. Cowdery unequivocally acknowledged the Twelve’s authority to lead the Church. He also commented on the nautical imagery used earlier by Elder Hyde in his conference discourse. Oliver said: ‘Bro. Hyde has just said that it was all important that we keep in the true channel in order to avoid the sandbars. This is true. The channel is here. The priesthood is here.'”95

Over the next several days, Oliver met with various leaders, including Elders Orson Hyde and George A. Smith, answering their questions and letting them know he was willing to receive counsel from the Twelve. He assured them that he had no desire for a leadership position, he just wanted to have his membership reinstated and be among and live with the Saints, and he also recognized the need to be rebaptized.96

On Sunday, November 5, 1848, Oliver met with the high council in the Kanesville Log Tabernacle. Oliver said he wanted to come into the Church in a humble manner, and be a humble follower of Jesus Christ, “not seeking any presidency.”97 He was subsequently baptized by Orson Hyde.98

Oliver’s death

Following his baptism, the First Presidency began giving Oliver various assignments, including working with Almon Babbit, Orson Hyde, and John Bernhisel “to petition Deseret to be admitted as a state.”99

However, Oliver’s declining health would not permit him to do anything more to forward the cause of the Church. His mother had died of tuberculosis when she was 43.100 Oliver died on March 3, 1850, when he was 44, and of the same disease as his mother. He died at the Peter Whitmer Sr. home in Missouri, surrounded by his wife and their only surviving daughter Maria; his brother-in-law David Whitmer; Hiram Page; his half-sister Lucy and her husband Phineas Young; and others of the Whitmer family.101

A few months before his death, Oliver was visited by Jacob Gates, a member of the Church and an acquaintance of Oliver’s before his excommunication in 1838. Jacob asked Oliver about his testimony that was printed in the Book of Mormon, and he wanted to know “if the testimony was based on a dream, the imagination of his mind, an illusion, or a myth.”102 Oliver responded, “Jacob, I want you to remember what I say to you. I am a dying man, and what would it profit me to tell you a lie? I know . . . that this Book of Mormon was translated by the gift and power of God. My eyes saw, my ears heard, and my understanding was touched, and I know that whereof I testified is true. It was no dream, no vain imagination of the mind—it was real.”103

Oliver’s legacy

In 1911, a monument was dedicated to Oliver Cowdery in Richmond, Missouri.104 The monument contains a brief and beautiful description of Oliver’s legacy:

Sacred to the memory of Oliver Cowdery, witness to the Book of Mormon and to the translation thereof by the gift and power of God.

Born 3rd October 1806, Wells, Rutland Co., Vermont. Died 3rd March, 1850, Richmond, Ray Co., Missouri.

He was the scribe of the translation as it fell from the lips of Joseph Smith, the Prophet. He copied the original manuscript for the printer’s use and was proof-reader of the first edition. He was the first person baptized in the Latter-day Dispensation of the Gospel; and was one of the six members of the Church of Jesus Christ as its organization, on the sixth day of April, A.D., 1830, at Fayette, Seneca Co., New York. Though separated from it for a time, he returned to the Church. He died firm in the faith.

This Monument has been raised in his honor by his fellow-believers; and also to commemorate the Testimony of Three Witnesses, the truth of which they maintained to he end of their lives. Over a million converts throughout the world have accepted their testimony and rejoince in their fidelity. Dedicated 1911.

References

- Richard Lloyd Anderson, “A Brief Biography of Oliver Cowdery,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), Kindle Edition; Larry E. Morris, “Oliver Cowdery’s Vermont Years and the Origin of Mormonism,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness. ↩︎

- Morris, “Oliver Cowdery’s Vermont Years and the Origin of Mormonism.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Larry E. Morris, “The Conversion of Oliver Cowdery,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), 4, https://rsc.byu.edu/days-never-be-forgotten-oliver-cowdery/conversion-oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Lucy Mack Smith, “The History of Joseph Smith by His Mother,” Zion’s Camp Books, Kindle Edition. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 6:22. ↩︎

- History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], p. 15, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/21?. ↩︎

- History, circa Summer 1832, p. 6, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-circa-summer-1832/6?. ↩︎

- Lucy Smith, “The History of Joseph Smith by His Mother.” ↩︎

- “The Timing of the Book of Mormon Translation,” https://discoverfaithinchrist.com/the-timing-of-the-book-of-mormon-translation/. ↩︎

- “The Testimony of the Three Witnesses,” in the Book of Mormon, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/bofm/three?lang=eng. ↩︎

- Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon, circa August 1829–circa January 1830, Page i, p. i, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/printers-manuscript-of-the-book-of-mormon-circa-august-1829-circa-january-1830/1#historical-intro. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 20:3. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 28:8. ↩︎

- Introduction to Doctrine and Covenants 28 (“Several members had been deceived by these claims, and even Oliver Cowdery was wrongly influenced thereby.”) ↩︎

- “Page, Hiram,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/hiram-page. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 28:2. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 32:1-3. ↩︎

- Richard Dilworth Rust, “A Mission to the Lamanites,” Revelations in Context, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/revelations-in-context/a-mission-to-the-lamanites?lang=eng. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Doctrine and Covenants 67. ↩︎

- See Doctrine and Covenants 69. ↩︎

- “Cowdery, Oliver,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Independent Printing Office Destroyed,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/event/independence-printing-office-destroyed. ↩︎

- “Cowdery, Oliver,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Church History in the Fulness of Times Student Manual, “Chapter Twelve: Zion’s Camp,” Salt Lake City, Utah, 2003, 142, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/church-history-in-the-fulness-of-times/chapter-twelve?lang=eng&id=p9#p9. ↩︎

- “Cowdery, Oliver,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- History, 1834–1836, p. 17, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1834-1836/19#facts. ↩︎

- Richard L. Bushman, “Oliver’s Joseph,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), https://rsc.byu.edu/days-never-be-forgotten-oliver-cowdery/olivers-joseph. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 18:37. ↩︎

- History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], p. 564, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-b-1-1-september-1834-2-november-1838/18. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Doctrine and Covenants 110. ↩︎

- Mark L. Staker, “Raising Money in Righteousness, Oliver Cowdery as Banker,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), https://rsc.byu.edu/days-never-be-forgotten-oliver-cowdery/raising-money-righteousness. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Cowdery, Oliver,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- Jeffrey N. Walker, “Oliver Cowdery’s Legal Practice in Tiffin, Ohio,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), https://rsc.byu.edu/days-never-be-forgotten-oliver-cowdery/oliver-cowderys-legal-practice-tiffin-ohio. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Church History in the Fulness of Times Student Manual, “Chapter Fifteen: The Church in Northern Missouri, 1836-38,” Salt Lake City, Utah, 2003, 184, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/church-history-in-the-fulness-of-times/chapter-fifteen?lang=eng&id=p17#p17. ↩︎

- Minutes, 12 April 1838, p. 119, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/minutes-12-april-1838/2. ↩︎

- Minutes, 12 April 1838, p. 119, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/minutes-12-april-1838/2. ↩︎

- Minutes, 12 April 1838, p. 123, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/minutes-12-april-1838/6. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Minutes, 12 April 1838, p. 126, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/minutes-12-april-1838/9. ↩︎

- Church History in the Fulness of Times Student Manual, “Chapter Fifteen: The Church in Northern Missouri, 1836-38,” Salt Lake City, Utah, 2003, 191, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/church-history-in-the-fulness-of-times/chapter-fifteen?lang=eng&id=p47#p47. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., Appendix 1: Letter to Oliver Cowdery and Others, circa 17 June 1838, p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/appendix-1-letter-to-oliver-cowdery-and-others-circa-17-june-1838/1. ↩︎

- Appendix 1: Letter to Oliver Cowdery and Others, circa 17 June 1838, p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/appendix-1-letter-to-oliver-cowdery-and-others-circa-17-june-1838/1. ↩︎

- Appendix 1: Letter to Oliver Cowdery and Others, circa 17 June 1838, p. 8, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/appendix-1-letter-to-oliver-cowdery-and-others-circa-17-june-1838/8. ↩︎

- Appendix 3: Discourse, circa 4 July 1838, p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/appendix-3-discourse-circa-4-july-1838/1. ↩︎

- Appendix 3: Discourse, circa 4 July 1838, p. 12, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 12, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/appendix-3-discourse-circa-4-july-1838/12. ↩︎

- “Cowdery, Oliver,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/oliver-cowdery. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Jeffrey N. Walker, “Oliver Cowdery’s Legal Practice in Tiffin, Ohio,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), https://rsc.byu.edu/days-never-be-forgotten-oliver-cowdery/oliver-cowderys-legal-practice-tiffin-ohio. ↩︎

- “Young, Phineas Howe,” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/phineas-howe-young. ↩︎

- Scott H. Faulring, “The Return of Oliver Cowdery,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), Kindle Edition. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. The records aren’t clear whether he was baptized on November 5, the same date as the high council meeting, or one week later on November 12. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Larry E. Morris, “Oliver Cowdery’s Vermont Years and the Origin of Mormonism,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), Kindle Edition. ↩︎

- Scott H. Faulring, “The Return of Oliver Cowdery,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), Kindle Edition. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Robert F. Schwartz, “The Dedication of the Oliver Cowdery Monument in Richmond Missouri, 1911,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, UT: The Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), Kindle Edition. ↩︎